The World’s Biggest Oil Kingdom Reverses Course

Javier Blass, Oct 19, 2016

In an effort to get prices off the mat, Saudi Arabia looks to pull back on the amount of crude it pumps.

Next year will be a test of strength for Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, as it tries to regain control of the market and lift prices. After two years of pumping at full blast, and helping drive prices to 12-year lows in January, the Saudis now appear willing to pull back. In September, at a meeting in Algiers, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries agreed to the outlines of a plan to lower the group’s production by as much as 750,000 barrels a day. Although the details won’t be final until the cartel’s Nov. 30 meeting in Vienna, the Saudis are expected to make most of those supply cuts.

The retreat signals an end to the kingdom’s foray into free-market economics. Two years ago, with prices already falling in response to a growing supply glut, Saudi Arabia, against the wishes of its fellow OPEC members, refused to lower output. The move was a direct challenge to other oil producers. By flooding the world with its low-cost crude, the Saudis bet that they could withstand lower prices longer than other countries and oil companies and force them out of the market. The strategy worked to a degree. The Saudis are pumping and selling record amounts of oil. Output hit almost 10.7 million barrels a day in July. At the same time, other producers have had to cut back: U.S. shale production has fallen, and non-OPEC oil supplies are set to drop in 2016 by the largest amount in 30 years.

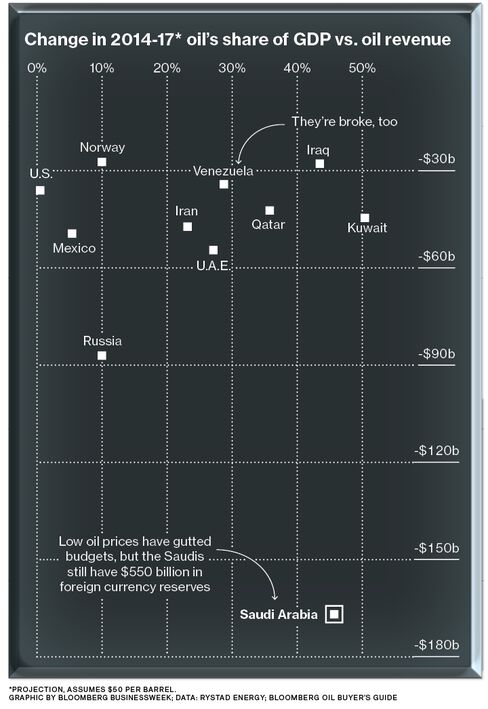

In April 2016 the powerful deputy crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, said the kingdom no longer cared whether oil cost $60 or $20 a barrel. Rather than keeping prices high, the Saudis seemed resigned to cheap oil and made plans to use that revenue to fund other investments in a bid to diversify the kingdom’s economy and reduce its reliance on crude. But the economic consequences of cheap oil have been severe for Saudi Arabia. Riyadh is burning through foreign-exchange reserves, government contractors have gone unpaid, and civil servants, who make up two-thirds of the labor force, will get no bonus this year. The country’s fiscal deficit is more than 10 percent of gross domestic product, the highest ratio of any Group of 20 nation. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that Saudi economic growth will slow to about 1 percent next year, the worst since 2009. A few banks predict a recession.

For the Saudis, it’s a fine line between prices that are too high and too low. “The deal in Algiers is a change of tack for Saudi Arabia and is a gamble that it can push prices higher without triggering a resurgence of shale production growth in the U.S.,” says Seth Kleinman, oil analyst at Citigroup. First, OPEC needs to agree on the specifics of the production limits, including which countries will reduce output and by how much. Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at consultant Energy Aspects in London, says OPEC ministers “have bought themselves two months to deliver, and they are fully aware of the cost of failure: Prices will fall sharply.” With Iran returning from sanctions and production from Nigeria and Libya limited by sabotage and war, those countries will most likely be exempt from the reductions; other OPEC countries will probably resist cutting their supplies, leaving it up to the Saudis to bear the burden of reducing output. “We expect that Saudi will shoulder the bulk of the production cuts,” says Neil Beveridge, oil analyst at researcher Sanford C. Bernstein in Hong Kong.

Even if OPEC irons out all the details in time for its Nov. 30 meeting in Vienna, the production decrease won’t affect the market until late January, at the earliest. Two weeks before OPEC announced its cut, the International Energy Agency presented a bearish outlook for 2017, writing that supply will continue to outpace demand at least through the first half of next year. The IEA also anticipates production from non-OPEC countries to rebound in 2017 and increase by 400,000 barrels a day. That’s a sign the global energy industry is learning to live with low prices by reducing costs.

Still, the Saudis are confident they will prevail. Khalid al-Falih, who became the country’s oil minister in May, told delegates of the World Energy Congress in Istanbul on Oct. 10 that a price recovery to $60 by the end of this year was “not unthinkable.”